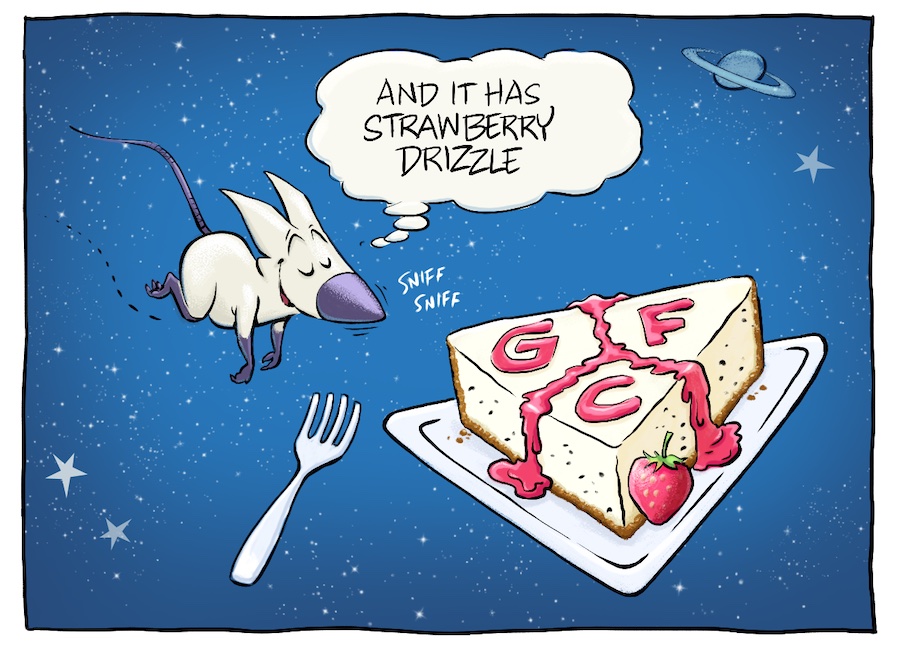

…a.k.a., the “Good, Fast, Cheap Triangle”

Life, as they say, is full of trade-offs. If Isaac Newton’s first law of thermodynamics teaches us anything, it is that time is money. Beds, once made, must be laid in (or is it “lied in”?…), and apparently nobody can have cake and eat it too.

Likewise, since primitive man’s earliest student short films, animation production has been plagued by the frustrating but immutable principle known as the “Good, Fast, Cheap Triangle”. The problem being that you can only have two:

Good and Fast, but not Cheap

Good and Cheap, but not Fast

or

Fast and Cheap, but not Good

It is a basic Law of the Universe. And so, naturally, we are trying to find a workaround. But no matter how talented our animators are, no matter how many quantum-calibrated hyper-dimensional combobulators we add to our render queue, and no matter how much coffee we consume, in the end we must face reality: you just can’t have all three.

“But it’s the year two-thousand something — don’t you have computers to do this stuff?“

Indeed, advances have been made. And no doubt our present-day techno-wizardry would blow the minds of our animation forefathers and foremothers. We can create dazzling computer-generated effects with unprecedented verisimilitude. And the vast armies of low-paid assistant animators cranking out heaping dumpster-fulls of pencil shavings have long-since been replaced by slightly smaller armies of slightly-more-highly-paid digital animators cranking out dumpster-fulls of ones and zeroes.

And certainly competition and raw creative genius propel the medium continually to new heights. But one thing hasn’t changed, and that is that good art takes time, and animation is a mind-bogglingly complex and process-driven art form that can only be accelerated up to a certain point, no matter how much money you throw at it (and anyway, nobody ever has more money to throw at it).

What are the options?

Still, there are a few things we can do to get at least within noseshot of that elusive, cosmic cheesecake. When presented with a challenging budget or schedule, we can usually provide options and alternatives – such as different animation styles and inventive ways to reduce the length or complexity of the piece (i.e. the “creative scope”) – that can still provide an excellent product without compromising the storytelling or the quality of the art and design.

For example, instead of producing a full 22-minute pilot for your TV series pitch, you might consider developing a shorter demo or animatic. Or that epic, three-minute web video concept may actually work great if shortened to one minute. And if the client already signed off on the creative and the budget is chiseled in stone, a flexible schedule can at least help us avoid overtime rates for evenings and weekends. There are a lot of factors involved in budgeting animation, some of which is described in this article. An experienced studio can walk you through the various options with plenty of relevant examples to consider.

But “simpler” doesn’t necessarily mean “lower quality”. And in that sense, we don’t think you should ever have to – nay, I say, we refuse to – compromise on quality. Harrumph! (Pounds fist on table.)

About the author: Sean Henry is Executive Producer and co-owner of Calabash Animation.

Contact Calabash Animation to get a customized quote for your project!